Those who have known Cranston teacher Nancy Sisti through the years are familiar with the quality of her historic character presentations. From Martha Washington to Mary Todd Lincoln and even Benjamin Franklin, Sisti has given generations

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account by clicking here.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

|

Those who have known Cranston teacher Nancy Sisti through the years are familiar with the quality of her historic character presentations.

From Martha Washington to Mary Todd Lincoln and even Benjamin Franklin, Sisti has given generations of students the opportunity to meet and greet historical characters without ever leaving their school buildings. She’s also a past winner of the Golden Apple Award, given to teachers who go above and beyond in their profession.

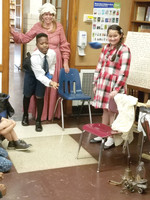

Last week, in one final encore presentation before her retirement this June, Sisti arrived at Gladstone Elementary School dressed in full character as her “cousin,” Miss Olsen, a pioneer teacher from the 1800s who traveled by covered wagon to teach out on the prairie in the western part of the country after having grown up in the whaling town of New Bedford, Mass., as the child of immigrant parents.

Miss Olsen greeted groups of four classes per hour, every hour, all day long, in the Gladstone library, where she had set up a table full of artifacts from the time period. The items included clothing, shoes, books, and other equipment and materials commonly used at that time.

She spoke to the students and their teachers about life on the prairie back in the days when she was teaching there. In past years, when Sisti had her own classroom, she would turn the entire room into an immersive learning opportunity for the students, teaching them as if it were the 1800s and they were her students in a one-room schoolhouse on the prairie.

She began by letting the students know how things have changed from then to now.

“You didn’t take your education lightly, it was a privilege to be in school,” she told the students. “You were lucky and you were thankful if your parents paid for you to get an education on the prairie, if they paid a teacher to come over from the east. You did not talk back, you were not allowed to. You’d be an embarrassment to your family. You used correct behavior, you had correct morals, you respected your teacher and your elders.”

She spoke of what it was like to be a teacher at that time.

“You did not want to be a burden to your family, so if you did not marry, you could be a nanny, you could work in a factory, you could be a companion to an older woman, a domestic servant, or you could be a teacher. If you married, you lost all of your rights. Your husband became the owner of all of your property. You had no votes and you had no right to divorce,” she said. “I decided to take a job as a teacher. They paid my way to come out from Boston by covered wagon, which I later used for firewood, because in the grasslands of Butte, Montana, there is no wood for fires. I taught my students reading, writing, arithmetic, and I gave them a good moral background. Students paid for their own books, and their books were handed down to their younger siblings.”

Miss Olsen explained that although the male school headmasters were allowed to marry, the female teachers were not, and if the teachers were caught talking to a male unsupervised, they were dismissed and sent back home.

“My day was a 12-hour day, and the school day itself was a 10-hour day,” she said. “There is an hour for lunch and recess, and most of the students walk five miles a day to school and back again in the winter and the summer. The spring and fall are for harvesting and planting crops. As a teacher I was expected to be completely covered every day of every season, and to wear two petticoats under my dress even in the summertime.”

She described the practice of “Boarding Round,” in which teachers were sent to live with the students’ families for a week at a time, where they were housed and fed for that week before moving on to the next student’s house.

“After five years, if I did a very good job, I was given a 25-cent raise,” she said. “I was expected to save every penny for retirement. I had no family, no children, and I retired when I simply could not physically work any longer.”

Olsen described classrooms with coal stoves in the middle of the room used for heat and classrooms infested with flies which were drawn in from the fertilizer used on the farmlands that surrounded the school. She explained that it was not only the teacher’s job to teach the children their academics and their morals, but also to check them daily for cleanliness of hands, feet, hair, and ears, as well as to teach the female students life skills such as sewing, embroidery and the preservation of food. The boys were taught the skills they’d need to survive on the prairie as farmers, such as when to harvest the crops and when to bring in the hay.

“The students in my classroom range from age four to 17 and from kindergarten to grade 12,” she said. “They used no paper, no pencils, but relied on memorization. If you were five minutes late to school you had to stay for an hour afterwards. Boys and girls entered the school from separate entrances.”

Throughout her presentation, Olsen interacted with both the teachers and the students, calling volunteers forward to try on period clothing or to participate in activities and games common for the time period, even teaching the children how to curtsy. She also invited the students to come to her presentation dressed in their best clothing, as was common practice for the time period. She took questions and answers at the end and allowed the students and staff to take a look at the various items she had on display.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here