Should Rhode Island’s children have a constitutional right to an education?

The U.S. Constitution doesn’t actually guarantee Americans the right to an education, according to legal …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account by clicking here.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

|

Should Rhode Island’s children have a constitutional right to an education?

The U.S. Constitution doesn’t actually guarantee Americans the right to an education, according to legal scholars. While some states have enshrined the right, via amendments to state constitutions, others, like Rhode Island, have tried but failed.

In July, the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council (RIPEC) issued a policy brief on changes to state education aid. To conclude the report, they urged the Ocean State to “adopt a constitutional right to education.”

Amending the Rhode Island constitution would legally require “equitable” state funding across the educational spectrum, for all students.

In 2021, Rhode Island’s legislators considered an education amendment. While it passed the state Senate, it died in the House. Speaker of Rhode Island’s House of Representatives K. Joseph Shekarchi did not support the amendment.

“I always keep an open mind, but I have not supported such an amendment in the past,” Shekarchi said last month. “Amending the Constitution in this way would open the state up to expansive litigation and inappropriately involve the judiciary in formulating education policy. Elected officials in the General Assembly are best suited to establish education policy and funding.”

RIPEC argues the legislature needs guidance.

“The General Assembly’s allocation of state education aid over the past three years constitutes a reversal of years of modest progress to make the state’s system of education finance more equitable,” according to RIPEC. “This experience serves as strong evidence that the adoption of a constitutional right to education is necessary to ensure that education funding is adequate and equitable for all students, and especially for students in the state’s poorest districts.”

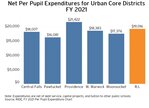

Several Rhode Island municipalities struggle with “property wealth much lower than the state overall and dramatically lower than some communities,” according to RIPEC. Those municipalities include Central Falls, Woonsocket, Pawtucket, Providence and West Warwick — the five “urban core districts” with the lowest “property wealth per capita” in the state.

“We must look to the states to determine which rights, if any, we have to an education,” attorney Trish Brennan-Gac wrote for the American Bar Association in 2014. “A limited number of state constitutions explicitly recognize education to be a fundamental right, entitling all students to the same quality of education regardless of neighborhood or income.”

Brennan-Gac’s research shows that prior to 1960, only two states recognized education as a fundamental right — Wyoming and North Carolina.

Maryland joined the shortlist in 1960, adding education to its Declaration of Rights, and California’s Supreme Court “started the ball rolling when its supreme court held in Serrano v. Priest (1976) that education is a fundamental right under its constitution,” she wrote. “Courts in Connecticut, Washington, and West Virginia soon followed suit. Mississippi, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Kentucky recognized the right to a quality education under their state constitutions in the 1980s.”

Courts in Alabama, Arkansas, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas recognized the decision, and “the movement picked up steam in the 1990s as 12 more state courts acknowledged a right to education,” Brennan-Gac wrote. “In 1993, Alabama, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Tennessee were added to the list, followed one year later by North Dakota and Virginia. By the end of the decade, Arkansas, Connecticut, Montana, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Vermont had joined the ranks.”

But not Rhode Island.

“Other state constitutions require the provision of education services (thorough and efficient education, etc.) by the state without conveying a right to students,” Brennan-Gac wrote. “Others barely address education at all. As a result, American education has developed into a hodge-podge quilt of different rights, access, and quality standards that depend entirely upon where children live.”

Threat of litigation necessary?

In Johnston, the town’s top school administrator supports the idea.

“I do support an amendment to the state constitution ensuring that all children have a right to an education,” said Superintendent Dr. Bernard DiLullo Jr. “In addition, the education has to be equitable among all children requiring adequate funding to meet the needs of all students.”

Johnston Schools have recently hired additional educators for specific sub-groups of students, like multilingual learners (MLL). The number of MLL students in Johnston jumped from 113 in 2015 to 270 in 2023, according to Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) data. RIPEC cited Rhode Island’s soaring MLL student populations in their report.

“Every child deserves the right to a good education,” Johnston Mayor Joseph M. Polisena Jr. said in October. “I would support such an amendment to the constitution if the General Assembly gave school committees their own taxing authority.”

Essentially, an argument for a Constitutional amendment revolves around funding, and how that funding is spread across all the school districts in the state.

“Even within states, school districts vary widely in resources and quality,” according to Brennan-Gac. “Some states rely heavily on local property taxes and wealth, while others allocate resources more equitably across all districts. The disparities have led to vastly different educational systems and outcomes. Parents and education activists from poor districts have turned to state constitutions for help.”

Many state legislators in Rhode Island support the idea, on both sides of the aisle.

“I see value in amending our state constitution to include the right to an adequate education,” Republican House Minority Leader state Rep. Mike Chippendale (District 40, Coventry, Foster and Glocester) said last month. “I have an appreciation for some of my colleagues’ hesitation regarding potential litigation that could arise if the right is enshrined, but when we’re looking at reports where certain schools in RI have an entire student body with 0% proficiency in math — we are beyond crisis-levels and need to react accordingly.”

According to RIDE Report Cards, MLL in the Coventry school district topped the Ocean State’s math proficiency charts, with 50%, becoming the only district in the state to reach the halfway mark. Coventry also had the state’s fourth-best MLL reading proficiency rates, at 26.7%.

“Perhaps the threat of litigation is precisely what’s needed to properly educate the children of our state,” Chippendale said. “While I do not want Rhode Island to be sued and the taxpayers to bear any of those cost(s) — I want a future with educated children and adults, and right now our public schools are failing to educate our children and that cannot stand.”

Change is Hard

Since public education is primarily funded by property tax revenues, the students educated in some Rhode Island public schools may receive a smaller-than-equitable slice of the state funding pie.

The Constitution of the State of Rhode Island includes two mechanisms for proposing and approving amendments. Article 14 of the state constitution prescribes either a constitutional amendment referred to electors by the state legislature or a constitutional convention.

If the General Assembly proposes an amendment, by roll call vote of a majority of members in each house, the constitutional revision can move on to the voters in the next General Election. The constitutional convention route also requires votes by the General Assembly, and the nomination of delegates to attend the convention. The voters must also approve any changes endorsed by the convention.

Rhode Island last convened a Constitutional Convention in 1986, which tackled, among other things, changes to the state’s position on the Right to Life/Abortion debate.

During the 2021 session, state Rep. Mary Messier and Sen. Roger Picard introduced H 5421 and S 205a, titled “Right to an Education.”

The bill passed the Rhode Island Senate but died in the House.

“For students in low-income communities, remedies for a lack of educational equity are particularly urgent,” according to ACLU Rhode Island. “This bill would have proposed an amendment to the Rhode Island constitution guaranteeing the right to an adequate education. The Rhode Island Supreme Court has several times rejected the notion that students have a judicially enforceable right to an education; this bill would have ensured and constitutionally established this right as fundamental.”

Former long-term substitute Spanish teacher State Rep. Enrique Sanchez’s (D-Dist. 9, Providence) constituents hail from neighborhoods like Silver Lake, Hartford Park, the West End and Olneyville. After teaching at schools including Providence Central High, Mt. Pleasant and Dr. Jorge Alvarez High School, the teacher-turned-legislator left the classroom supporting the amendment.

“We need to pass it,” Sanchez said. “Pushing for a constitutional amendment is progressive policy … It creates a more pro-public education friendly environment for the public schools … It would guarantee every student in the state the right (to) an education.”

The Search for Equitable State Funding

RIPEC has sounded the alarm bell that the state’s public education funding formula may not be equitably serving the state’s students who live in the “urban core districts,” where about one-third of the state’s students are enrolled. According to the agency, those communities received “less than half (49.5 percent) of all new funding from FY 2021 to FY 2024, as compared to receiving 59.3 percent of increased funding over the ten-year phase-in period of the funding formula.”

While the state’s funding formula seemed to trend in the right direction when it was first phased in during FY 2021, allocations from the past two years have slipped backward.

“Ironically, the first year in which the funding formula became fully phased in was the last year in which the formula operated as intended,” explained Michael DiBiase, President and CEO of RIPEC. “While the General Assembly made some positive changes, the FY 2024 funding formula consists of a multiplicity of modifications that are complicated and fail to reflect a coherent or consistent policy. The result is a patchwork of funding allocations that appear to make little sense when comparing funding outcomes for communities that are similar in terms of student demographics and their relative ability to raise local revenue for their schools.”

RIPEC urges the General Assembly to “pursue comprehensive reform of the funding formula.”

Polisena argues for a “total overhaul” of the state’s education system and funding mechanisms.

“Taxpayers should be able to discern and differentiate what their school department is spending vs what their municipality is spending,” Polisena wrote via email. “So for example, if a school is half of a municipal budget like it is in Johnston ($65m of $130m), if you paid a $5,000 property tax bill, going forward that bill would morph into two $2,500 bills then residents could track which bills go up, when and why.”

Johnston’s mayor argues statewide funding reform may be a more important priority than a change to the state’s constitution.

“Furthermore, a constitutional amendment like this has zero bearing on what a child is learning, or unfortunately as is the case today, not learning, inside the classroom,” Polisena said. “There needs to be a total overhaul of the education system not just in Rhode Island, but the United States. I don’t know how many more studies need to come out that show the United States lagging behind other developed countries in education before someone actually does something to fix it.”

Learning While Learning the Language

Another closely related realm of concern raised by RIPEC, and echoed in a new report in early October, involves the state’s booming MLL population.

Many of the towns and cities with the lowest per capita property wealth rates in the state also have the highest influx of English language learners entering their public school systems.

In 2023, Central Falls became the first district in Rhode Island “with more than half its students classified as multilingual learners.” A “constitutional right” to an education would require equitable state funding for districts that are so far failing to educate those populations adequately when compared to national test score averages.

RIPEC recommends the General Assembly incorporate funding for multilingual learners directly into the state funding formula, rather than handling it as a supplemental funding item.

“Moreover, it is unclear whether this funding is adequate given the state’s large and growing population of multilingual learners,” RIPEC further warns.

Johnston State Rep. Deb Fellela supports a tweak to the state’s population to help the most vulnerable learners among her constituency and across the Ocean State.

“I do believe that is the rights of all the children to receive an education, I would support such amendment,” Fellela said last month. “I've seen the population changing in the past few years, so we do need to make accommodations for these students. No students should be left behind.”

PREAMBLE to the Constitution of the State of Rhode Island

We, the people of the State of Rhode Island, grateful to Almighty God for the civil and religious liberty which He hath so long permitted us to enjoy, and looking to Him for a blessing upon our endeavors to secure and to transmit the same, unimpaired, to succeeding generations, do ordain and establish this Constitution of government.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here